Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works by A. G. Lafley, Roger L. Martin

Highlighted sections

strategy is about making specific choices to win in the marketplace.

In short, strategy is choice. More specifically, strategy is an integrated set of choices that uniquely positions the firm in its industry so as to create sustainable advantage and superior value relative to the competition.

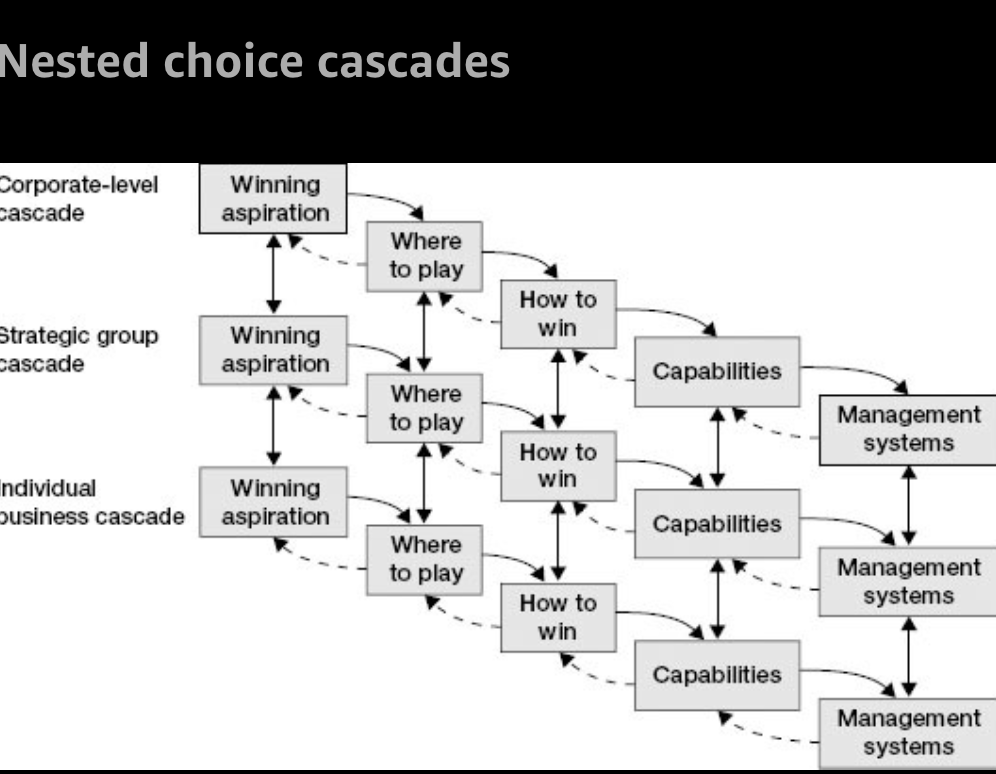

a strategy is a coordinated and integrated set of five choices: a winning aspiration, where to play, how to win, core capabilities, and management systems.

Strategy needn’t be mysterious. Conceptually, it is simple and straightforward. It requires clear and hard thinking, real creativity, courage, and personal leadership. But it can be done.

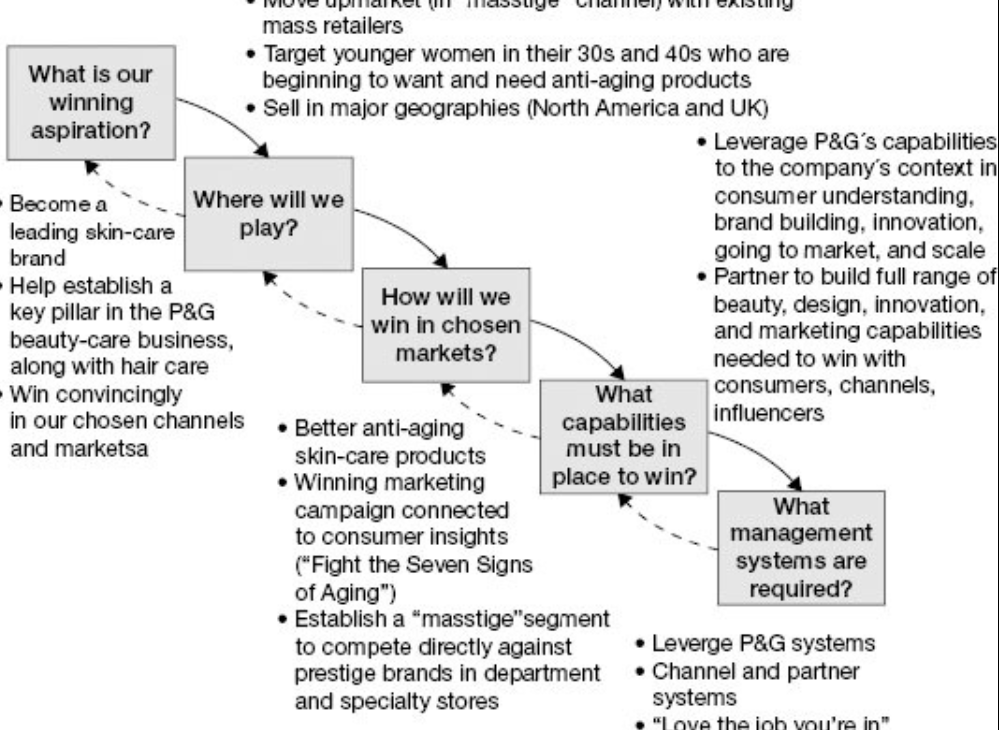

Olay had a strategic problem that many companies struggle with—a stagnant brand, aging consumers, uncompetitive products, strong competition, and momentum in the wrong direction.

What is your winning aspiration? The purpose of your enterprise, its motivating aspiration. Where will you play? A playing field where you can achieve that aspiration. How will you win? The way you will win on the chosen playing field. What capabilities must be in place? The set and configuration of capabilities required to win in the chosen way. What management systems are required? The systems and measures that enable the capabilities and support the choices.

Aspirations are statements about the ideal future. At a later stage in the process, a company ties to those aspirations some specific benchmarks that measure progress toward them.

Aspirations can be refined and revised over time. However, aspirations shouldn’t change day to day; they exist to consistently align activities within the firm, so should be designed to last for some time. A definition of winning provides a context for the rest of the strategic choices; in all cases, choices should fit within and support the firm’s aspirations.

The next two questions are where to play and how to win. These two choices, which are tightly bound up with one another, form the very heart of strategy and are the two most critical questions in strategy formulation. The winning aspiration broadly defines the scope of the firm’s activities; where to play and how to win define the specific activities of the organization—what the firm will do, and where and how it will do this, to achieve its aspirations.

The questions to be asked focus on where the company will compete—in which markets, with which customers and consumers, in which channels, in which product categories, and at which vertical stage or stages of the industry in question.

Where to play selects the playing field; how to win defines the choices for winning on that field. It is the recipe for success in the chosen segments, categories, channels, geographies, and so on.

To determine how to win, an organization must decide what will enable it to create unique value and sustainably deliver that value to customers in a way that is distinct from the firm’s competitors.

Two questions flow from and support the heart of strategy: (1) what capabilities must be in place to win, and (2) what management systems are required to support the strategic choices?

The final strategic choice in the cascade focuses on management systems. These are the systems that foster, support, and measure the strategy. To be truly effective, they must be purposefully designed to support the choices and capabilities.

Do make your way through all five choices. Don’t stop after defining winning, after choosing where to play and how to win, or even after assessing your capabilities. All five questions must be answered if you are to create a viable, actionable, and sustainable strategy.

What Is Winning

Starbucks mission statement: “To inspire and nurture the human spirit—one person, one cup, and one neighborhood at a time.”

Nike’s: “To bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete* in the world.” (The additional note, indicated by the asterisk, reads: “*If you have a body, you’re an athlete.”)

And McDonald’s: “Be our customers’ favorite place and way to eat.”

The first box in the strategic choice cascade—what is our winning aspiration?—defines the purpose of your enterprise, its guiding mission and aspiration, in strategic terms. What does winning look like for this organization? What, specifically, is its strategic aspiration? These answers are the foundation of your discussion of strategy; they set the context for all the strategic choices that follow.

As a rule of thumb, though, start with people (consumers and customers) rather than money (stock price). Peter Drucker argued that the purpose of an organization is to create a customer, and it’s still true today.

a company must play to win. To play merely to participate is self-defeating. It is a recipe for mediocrity. Winning is what matters—and it is the ultimate criterion of a successful strategy.

Lots of companies try to win and still can’t do it. So imagine, then, the likelihood of winning without explicitly setting out to do so.

To set aspirations properly, it is important to understand who you are winning with and against. It is therefore important to be thoughtful about the business you’re in, your customers, and your competitors.

We wanted them to focus outward on their most important consumers and very best competitors,

Many handheld phone manufacturers, for example, would say they are in the business of making smartphones. They would not likely say that they are in the business of connecting people and enabling communication any place, any time.

Or think of a skin-care company. It is far more likely to say it makes a line of skin-care products than to say it is in the business of helping women have healthier, younger-looking skin or helping women feel beautiful.

Look at your biggest competitors, your historical competitors—for P&G, they are Unilever, Kimberly-Clark, and Colgate-Palmolive. But then expand your thinking to focus on the best competitor in your space, looking far and wide to determine just who that competitor might be.

“Who really is your best competitor? More importantly, what are they doing strategically and operationally that is better than you? Where and how do they outperform you? What could you learn from them and do differently?”

Without explicit where-to-play and how-to-win choices connected to the aspiration, a vision is frustrating and ultimately unfulfilling for employees. The company needs where and how choices in order to act. Without them, it can’t win.

Do craft aspirations that will be meaningful and powerful to your employees and to your consumers; it isn’t about finding the perfect language or the consensus view, but is about connecting to a deeper idea of what the organization exists to do.

Where-to-play choices occur across a number of domains, notably these: Geography. In what countries or regions will you seek to compete? Product type. What kinds of products and services will you offer? Consumer segment. What groups of consumers will you target? In which price tier? Meeting which consumer needs? Distribution channel. How will you reach your customers? What channels will you use? Vertical stage of production. In what stages of production will you engage? Where along the value chain? How broadly or narrowly?

a company should make its where-to-play choices with the competition firmly in mind. Choosing a playing field identical to a strong competitor’s can be a less attractive proposition than tacking away to compete in a different way, for different customers, or in different product lines. But strategy isn’t simply a matter of finding a distinctive path. A company may choose to play in a crowded field or in one with a dominant competitor if the company can bring new and distinctive value. In such a case, winning may mean targeting the lead competitor right away or going after weaker competitors first.

you should avoid three pitfalls when thinking about where to play. The first is to refuse to choose, attempting to play in every field all at once. The second is to attempt to buy your way out of an inherited and unattractive choice. The third is to accept a current choice as inevitable or unchangeable.

Low-Cost Strategies

In cost leadership, as the name suggests, profit is driven by having a lower cost structure than competitors do.

Only the true low-cost player can win with a low-cost strategy.

Differentiation Strategies

products or services that are perceived to be distinctively more valuable to customers than are competitive offerings,

Each brand or product offers a specific value proposition that appeals to a specific group of customers.

Differentiation between products is driven by the activities of the firm: product design, product performance, quality, branding, advertising, distribution, and so on.

The more a product is differentiated along a dimension consumers care about, the higher price premium it can demand.

All successful strategies take one of these two approaches, cost leadership or differentiation.

You don’t get to be a cost leader by producing your product or service exactly as your competitors do, and you don’t get to be a differentiator by trying to produce a product or service identical to your competitors’

Many companies like to describe themselves as winning through operational effectiveness or customer intimacy. These sound like good ideas, but if they don’t translate into a genuinely lower cost structure or higher prices from customers, they aren’t really strategies worth having.

a strong where-to-play choice is only valuable if it is supported by a robust and actionable how-to-win choice.

Cost leaders can create advantage at many different points—sourcing, design, production, distribution, and so on. Differentiators can create a strong price premium on brand, on quality, on a particular kind of service, and so forth.

Structuring a company to compete as a cost leader requires an obsessive focus on pushing costs out of the system, such that standardization and systemization become core drivers of value. Anything that requires a distinctive approach is likely to add cost and should be eliminated.

In a differentiation strategy, costs still matter, but are not the focus of the company; customers are. The most important question is how to delight customers in a distinctive way that produces greater willingness to pay.

An organization’s core capabilities are those activities that, when performed at the highest level, enable the organization to bring its where-to-play and how-to-win choices to life.

Identifying the capabilities required to deliver on the where-to-play and how-to-win choices crystallizes the area of focus and investment for the company. It enables a firm to continue to invest in its current capabilities, to build up others, and to reduce the investment in capabilities that are not essential to the strategy.

When thinking about capabilities, you may be tempted to simply ask what you are really good at and attempt to build a strategy from there. The danger of doing so is that the things you’re currently good at may actually be irrelevant to consumers and in no way confer a competitive advantage. Rather than starting with capabilities and looking for ways to win with those capabilities, you need to start with setting aspirations and determining where to play and how to win. Then, you can consider capabilities in light of those choices. Only in this way can you see what you should start doing, keep doing, and stop doing in order to win.

Once the capabilities were articulated, the team then spent most of the day deciding how and where to begin investing in each capability to broaden and deepen competitive advantage. It wrote an action plan for each of the five capabilities to create competitive advantage at the corporate, category, and brand levels.

In this system, the core capabilities are shown as large nodes, and the links between the large nodes represent important reinforcing relationships. These reinforcing relationships make each capability stronger, which is an essential characteristic of an activity system: the system as a whole is stronger than any of the component capabilities, insofar as those capabilities fit with and reinforce one another.

In addressing feasibility, ask several questions: is this a realistic activity system to build? How much of it is currently in place, and how much would you have to create? For the capabilities you would need to build, is it affordable to do so? If upon reflection, you find that the activity system isn’t feasible, then you need to reconsider where to play and how to win.

When you have a feasible activity system, you can ask more questions: is it distinctive? Is it similar to or different from competitors’ systems? This is an important point. Imagine that a competitor has a different where-to-play and how-to-win choice, but a very similar set of capabilities and supporting activities. In such a situation, the competitor could shift to your potentially superior where-to-play and how-to-win choices and begin to cut in to your competitive advantage. If the activity system isn’t distinctive, the where and the how and the map must be revisited until such time as a distinctive combination emerges. As Porter notes, not all of the elements need to be unique or impossible to replicate. It is the combination of capabilities, the activity system in its entirety, that must be inimitable.

When it has a feasible and distinctive activity system, you can ask, is the system defensible against competitive action? If the system can be readily replicated or overcome, then the overall strategy is not defensible and won’t provide meaningful competitive advantage. In that case, you need to revisit your where-to-play and how-to-win choices to find a set of strategic choices and an activity system that are difficult to replicate and hard to defend against.

The activity system should be feasible, distinctive, and defensible if it is to enable you to win. If the system is missing any of these three qualities, you need to return to the where-to-play and how-to-win choices, refining or even entirely changing those choices until they result in a distinctive and winning activity system.

“I have a view worth hearing, but I may be missing something.” It sounds simple, but this stance has a dramatic effect on group behavior if everyone in the room holds it. Individuals try to explain their own thinking—because they do have a view worth hearing. So, they advocate as clearly as possible for their own perspective. But because they remain open to the possibility that they may be missing something, two very important things happen. One, they advocate their view as a possibility, not as the single right answer. Two, they listen carefully and ask questions about alternative views. Why? Because, if they might be missing something, the best way to explore that possibility is to understand not what others see, but what they do not.

This approach includes three key tools: (1) advocating your own position and then inviting responses (e.g., “This is how I see the situation, and why; to what extent do you see it differently?”); (2) paraphrasing what you believe to be the other person’s view and inquiring as to the validity of your understanding (e.g., “It sounds to me like your argument is this; to what extent does that capture your argument accurately?”); and (3) explaining a gap in your understanding of the other person’s views, and asking for more information (e.g., “It sounds like you think this acquisition is a bad idea. I’m not sure I understand how you got there. Could you tell me more?”).

No individual, and certainly not the CEO, would try to craft and deliver a strategy alone. Creating a truly robust strategy takes the capabilities, knowledge, and experience of a diverse team—a close-knit group of talented and driven individuals, each aware of how his or her own effort contributes to the success of the group and all dedicated to winning as a collective.

Since strategic choice is a judgment call in which nobody can prove that a particular strategy is right or the best in advance, there is a fundamental challenge to coming to organizational decisions on strategy. Everyone selects and interprets data about the world and comes to a unique conclusion about the best course of action. Each person tends to embrace a single strategic choice as the right answer. That naturally leads to the inclination to attack the supporting logic of opposing choices, creating entrenchment and extremism, rather than collaboration and deep consideration of the ideas.

A massive binder or thick PowerPoint deck won’t rally an organization. So it is important to think explicitly about the core of a strategy and the best way to communicate its essence broadly and clearly. Ask, what are the critical strategic choices that everyone in the organization should know and understand?

While the messages themselves were pivotal for embedding the strategic intent in the organization, so too was the language used to convey them. It was simple, evocative, and memorable. In any organization, the choices at the top must be precisely and evocatively stated, so that they are easily understood. Only when the choices are clear and simple can they be acted upon—only then can they effectively shape choices throughout the rest of the organization.

For measures to be effective, it is crucial to indicate in advance what the expected outcomes are. Be explicit: “The following aspiration, where to play, how to win, capabilities, and management systems should produce the following specific outcomes.” Expected outcomes should be noted in writing, in advance. Specificity is crucial. Rather than stating “increase in market share” or “market leadership,” quantify a thoughtful range within which you would declare success and below which you would not. Without such defined measures, you can fall prey to the human tendency to rationalize any outcome as more or less what you expected.

Within an organization, every business unit or function should have specific measures that relate to the organizational context and that unit’s own choices.

These measures should span financial, consumer, and internal dimensions, to prevent the team from focusing exclusively on a single parameter of success.

One of the biggest lessons I had learned in my years at P&G was the power of simplicity and clarity. I found that clearer, simpler strategies have the best chance of winning, because they can be best understood and internalized by the organization. Strategies that can be explained in a few words are more likely to be empowering and motivating; they make it easier to make subsequent choices and to take action.

rather than dwell on crafting the perfect definition of winning, sketch a prototype, with the understanding that you will return to it later with the rest of the cascade in mind.

Ultimately, there are four dimensions you need to think about to choose where to play and how to win: The industry. What is the structure of your industry and the attractiveness of its segments? Customers. What do your channel and end customers value? Relative position. How does your company fare, and how could it fare, relative to the competition? Competition. What will your competition do in reaction to your chosen course of action?

You must ask, what might be the distinct segments of the industry in question (geographically, by consumer preference, by distribution channel, etc.)? Which segmentation scheme makes the most sense for the given industry today, and what might make sense in the future? And what is the relative attractiveness of those segments, now and in the future?

The vertical axis—threat from new entrants and threat of substitute products—determines how much value is generated by the industry (and is therefore available to be split up among industry players). If it is very difficult for new players to enter the industry and there are no substitutes to the industry’s product or services to which buyers can turn, then the industry will generate high value. ^ref-11482

The horizontal axis determines which entity will capture the industry value—suppliers, producers, or buyers. If the suppliers are larger and more powerful than the producers, the suppliers will appropriate more of the value (think Microsoft and Intel in the PC business). If, on the other hand, the buyers are large and powerful, they will get a greater portion of the value (think Walmart versus the many small manufacturers whose products fill their shelves).

Any new strategy is created in a social context—it isn’t devised by an individual sitting alone in an office, thinking his or her way through a complex situation.

It begins with framing the fundamental choice, articulating at least two different ways forward for the organization (or category, function, brand, product, etc.), on the basis of your winning aspiration. Then, the team works to brainstorm a wider variety of possible strategic choices, different where-to-play and how-to-win choice combinations that could result in winning. These strategic possibilities are then each considered in turn by asking what would have to be true for this possibility to be a potentially winning choice.

Next, the group reflects on the set of conditions and asks which of those conditions seem the least likely to hold. These least-likely-to-be-true conditions are the barriers to selecting a given option;

As a general rule, an issue—for example, declining sales or technology change in the industry—can’t be resolved until it is framed as a choice.

To frame the choice, explicitly ask, what are the different ways of resolving this problem? Work to generate several options that stand in opposition to one another (i.e., such that you could not easily pursue the different remedies at the same time).

Generate Strategic Possibilities

In this context, a possibility should be expressed as a narrative or scenario, a happy story that describes a positive outcome.

The possibilities generated may be related to the options already identified, as either amplifications or nuances.

The possibilities can also expand further beyond the original two options.

Notice, this step is decidedly not for arguing about what is true, but rather for laying out the logic of what would have to be true for the group to collectively commit to a choice.

frame the choice, understand the conditions, order the barriers, and analyze only the binding constraints

That, in sum, is the process for choosing between possibilities for where to play and how to win. First, frame a choice. Second, explore possibilities to broaden the set of mutually exclusive possibilities. Third, for each possibility, ask, what would have to be true for this to be a great idea, using the logic flow framework to structure your thinking. Fourth, determine which of the conditions is the least likely to actually hold true. Fifth, design tests against those crucial barriers to choice. Six, conduct tests. Finally, in light of the outcome of the tests and how those outcomes stack up against predetermined standards of proof, select the best strategic choice possibility.

In this moment, the best role of the consultant became clear to me: don’t attempt to convince clients which choice is best; run a process that enables them to convince themselves.

Six Strategy Traps There is no perfect strategy—no algorithm that can guarantee sustainable competitive advantage in a given industry or business. But there are signals that a company has a particularly worrisome strategy. Here are six of the most common strategy traps: The do-it-all strategy: failing to make choices, and making everything a priority. Remember, strategy is choice. The Don Quixote strategy: attacking competitive “walled cities” or taking on the strongest competitor first, head-to-head. Remember, where to play is your choice. Pick somewhere you can have a chance to win. The Waterloo strategy: starting wars on multiple fronts with multiple competitors at the same time. No company can do everything well. If you try to do so, you will do everything weakly. The something-for-everyone strategy: attempting to capture all consumer or channel or geographic or category segments at once. Remember, to create real value, you have to choose to serve some constituents really well and not worry about the others. The dreams-that-never-come-true strategy: developing high-level aspirations and mission statements that never get translated into concrete where-to-play and how-to-win choices, core capabilities, and management systems. Remember that aspirations are not strategy. Strategy is the answer to all five questions in the choice cascade. The program-of-the-month strategy: settling for generic industry strategies, in which all competitors are chasing the same customers, geographies, and segments in the same way. The choice cascade and activity system that supports these choices should be distinctive. The more your choices look like those of your competitors, the less likely you will ever win. These are strategic traps to be aware of as you craft a strategy for your organization. But there are also signs that you have found a winning and defensible strategy. Let’s look at these next.

Six Telltale Signs of a Winning Strategy Because the world is so complex, it is hard to tell definitely which results are due to the strategy, which to macro factors, and which to luck. But, there are some common signs that a winning strategy is in place. Look for these, for your own business and among your competitors. An activity system that looks different from any competitor’s system. It means you are attempting to deliver value in a distinctive way. Customers who absolutely adore you, and noncustomers who can’t see why anybody would buy from you. This means you have been choiceful. Competitors who make a good profit doing what they are doing. It means your strategy has left where-to-play and how-to-win choices for competitors, who don’t need to attack the heart of your market to survive. More resources to spend on an ongoing basis than competitors have. This means you are winning the value equation and have the biggest margin between price and costs and the best capacity to add spending to take advantage of an opportunity or defend your turf. Competitors who attack one another, not you. It means that you look like the hardest target in the (broadly defined) industry to attack. Customers who look first to you for innovations, new products, and service enhancement to make their lives better. This means that your customers believe that you are uniquely positioned to create value for them.